With our archives now 3,500+ articles deep, we’ve decided to republish a classic piece each Sunday to help our newer readers discover some of the best, evergreen gems from the past. This article was originally published in October 2013.

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post written by Khaled Allen.

As a little boy, I was scrawny, weak, and prone to illness (much like a certain former president). For a long time, I thought I was just doomed to be pathetic, until my dad took me canoeing. In the mucky, hot, poorly maintained trails and portages of the Boundary Waters in the north woods of Minnesota, I learned that I could be tough, scrappy, and indomitable. I took a brutal pleasure in carrying the heaviest pack I could over long and steep portages, willing my toothpick legs to take one step, then another, then another, until I saw the blue expanse of the next lake peeking through the trees. That was all I had to work with: a willingness to push myself harder than anyone else, to charge headlong into the roughest terrain, and to ignore cold, rain, heat, bugs, and my own internal discomfort.

With the popularity of high-intensity workout programs, military-inspired training, and brutal adventure races, mental toughness is in the spotlight. The gold standard of a hardcore athlete is how much pain they can tolerate. But what about simple, plain old ruggedness? What does it mean to be physically tough, as well as mentally tough? Is it enough to simply be strong, or is there something more to it?

Strong But Weak

I will always remember the day I dropped in on a CrossFit class and went out for the warm-up jog with no shoes on. One of the other guys there, massively strong and musclebound, was shocked and asked me if it hurt or if I was scared of broken glass. I explained that I’d toughened up my feet over the last few years and it didn’t bother me at all. If I was caught shoeless in an emergency, the few seconds I needed to put on shoes could make the difference between life and death. It didn’t matter how fast I could sprint if my feet were too tender to handle the asphalt.

I see that reaction all the time: big guys with lots of muscles who wince as soon as the shoes come off or who insist on wearing gloves whenever they lift weights. They are immensely strong within their particular domain, but have very strict limits on their comfort zone. As soon as they are forced out of it, their performance drops drastically.

Defining Toughness

Men in particular often confuse toughness with strength, thinking that being strong is automatically the same as being tough, when in fact the two are distinct qualities. As Erwan Le Corre, founder of MovNat, says, “Some people with great muscular strength may lack toughness and easily crumble when circumstances become too challenging. On the other hand, some people with no particularly great muscular strength may be very tough, i.e., capable of overcoming stressful, difficult situations or environments.”

Toughness is the ability to perform well regardless of circumstances. That might mean performing well when you are sick or injured, but it also might mean performing well when your workout gear includes trees and rocks instead of pull-up bars and barbells. “Toughness . . . is the strength, or ability, to withstand adverse conditions,” according to Le Corre.

Being able to do that requires both mental and physical toughness. No amount of mental toughness alone will keep you from freezing in cold temperatures, but if you’ve combined mental training with cold tolerance conditioning, for example, then you’ll fare much better.

Toughness Is a Skill

It is a myth that you’re either born tough or you’re not. The truth is, toughness, both mental and physical, can and should be trained and cultivated, just like any other skill. There are certain mental techniques that help you cultivate an indomitable will, patience, and the ability to stay positive and focused no matter how bad things look. There are also certain training techniques you can use to condition your body to withstand discomfort and tolerate environments that would normally cause injury.

Mental Toughness

Mental toughness boils down to how you respond to stress. Do you start to panic and lose control, or do you zero in on how you are going to overcome the difficulty?

Rachel Cosgrove, co-owner of Results Fitness and a regular contributor to Men’s Fitness, stated in an article on mental toughness, “World-class endurance athletes respond to the stress of a race with a reduction in brain-wave activity that’s similar to meditation. The average person responds to race stress with an increase in brain-wave activity that borders on panic.”

Similarly, the biggest determining factor in whether or not a candidate for the Navy SEALs passes training is his ability to stay cool under stress and avoid falling into that fight-or-flight response most of us drop into when we’re being shot at. Developing ways to counteract the negative response to stress helps us stay in control of our bodies so that we can maintain the high performance needed to do well in any situation. That is real mental toughness.

Another way to look at mental toughness is willpower. When everyone else has decided they are too tired, you decide to keep going. In sports, this is called the second wind, when an athlete determines that they don’t care about their fatigue and decides to push harder despite it. When a football team is behind two touchdowns but picks up the effort anyway, determined to win despite all signs to the contrary, that’s an example of willpower in action. They may still lose, but they are much more likely to make a comeback with this approach.

So, how can you cultivate mental toughness?

Small Discomforts

One of the best ways to develop mental toughness is to accept small discomforts on a regular basis. Take only cold showers or occasionally fast. In the book Willpower, Dr. Roy Baumeister recounts the training regimen of famed endurance artist David Blaine. Before doing his stunts — some of which have included being encased in ice for over 63 hours, being suspended over the Thames in a clear plastic box for 44 days, and holding his breath for 17 minutes on live TV — Blaine will start to make up little inconvenient routines for himself simply to strengthen his willpower. These are usually small things, like touching every overhanging tree branch on his walk to work, but they get his mind in the habit of making extra effort even when he doesn’t feel like it, exercising will, and doing things when it would be inconvenient or uncomfortable.

Examples of this include sticking to an inconvenient diet, living without a car, or shaving with a straight razor.

There’s a lot to be said for simple acclimatization to discomfort as well. The little nicks and bruises you get from training in wild environments can be hugely distracting when you’re just getting started, but if you keep heading back out, you eventually find them little more than useful feedback on positioning and technique.

Think Positive

Most of us have an internal monologue going on in our heads, telling our own story. How this sounds depends on our view of ourselves and external stimuli. If you’ve always been good at schoolwork, you might envision yourself as “smart,” but maybe not “strong” or “charming.”

The thing is, these definitions are mostly arbitrary. Anyone who works hard enough at academics can do well in school, and anyone who trains hard enough can do well in sports. Whether or not we are willing and able to push ourselves hard enough to do well often depends on that internal story.

So, the simple solution is to only accept positive self-talk. This is a common tactic of the super-successful, and is standard fare in such personal development classics as Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People, Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich, and Stephen R. Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

Have a Reason

One of the most powerful motivators in training and life is knowing why you cannot fail. Jack Yee, who writes specifically about mental toughness and has been featured on T-Nation and Mark’s Daily Apple, remembers his time at the famous Gold’s Gym in Venice Beach, where he saw not only old school greats like Tom Platz, Lou Ferrigno, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, but also a large number of promising amateurs, many of whom had more impressive physiques. However, they rarely lasted long: after one defeat at a competition, they would give up. One discouraging setback was enough to shatter their confidence.

The antidote is to remind yourself why you’re out there in the first place. A common trick I used to use in my running when I was feeling defeated was to imagine that my girlfriend was being threatened by kidnappers and if I didn’t get to her in time, they would kill her. Since my motivation for exercising was to be useful to those I cared about, this worked for me. No matter how beat up I felt, I would always run faster.

Mental Toughness Training Summary

- Allow (or seek out) small inconveniences and discomforts in your everyday life. Learn to tolerate them.

- Start to judge your internal monologue, rather than simply accepting it for what it is. Actually listen to what you’re saying and decide if it’s a belief you want to let into your life.

- When you’re feeling tired and talking yourself out of your workout, remind yourself why you’re training. Weigh the importance of the inconvenience against the importance of the why and get out there.

Physical Toughness

Compared to mental toughness, there is considerably less talk about physical toughness out there, probably because it is wrapped up into strength and conditioning. But the truth is, being physically tough is very different from being strong, fast, or powerful. Physical toughness includes the ability to take abuse and keep functioning, to recover quickly, to adapt to difficult terrain and contexts, and to tolerate adverse conditions without flagging.

Le Corre’s method of training, MovNat, emphasizes the value of developing a tough body by training in environments that do not accommodate the trainee. Training outdoors, in adverse (or simply not climate-controlled) conditions, is a core tenet of MovNat’s methods. Le Corre says of physical toughness, “[it] is the ability of the body to withstand hardship, such as food or sleep deprivation, harsh weather conditions such as cold, heat, rain, snow or humidity, and difficult terrains (steep, rocky, slippery, radiating heat, dense vegetation etc.).”

Physical toughness boils down to the changes your body makes to make it more resilient. This has the effect of unloading your willpower so that you can push yourself harder mentally, since your threshold has effectively increased.

Thicker Skin

A very simple example of physical toughness — and one that is used as a euphemism for toughness in general — is thick skin. Men who train hard in gyms rarely develop calluses beyond those along the base of the fingers that are the result of the bar pinching the grip. Men who train with tough objects, like stones, logs, or in nature tend to develop thick skin all over their fingers and palms. The same goes for the feet. Accompanying this change is an alteration in the sensitivity of the pain receptors in those areas. As you become accustomed to walking barefoot, what used to be painful becomes a comfortable massage.

Exposure to the elements is the best way to develop this very real form of physical toughness. Train barefoot with minimal clothing, with rough implements. Start with shorter durations and forgiving surfaces so you don’t get to the point of actual injury, and increase the time and ruggedness of the environment. You will learn to tell the difference between discomfort and real pain. You’ll also learn how to be gentle when dealing with rock and dirt, but you’ll get tougher as well.

Supple Joints

An oft-overlooked form of toughness combines mobility, flexibility, and durability. Hard training puts a lot of stress on the body, but this stress is multiplied when every movement stretches a muscle close to its full range or pushes a joint near its limit. Flexible joints can move farther without incurring stress on their support structures, reducing fatigue and the wear and tear that adds up to leave you sore and whimpering on the ground.

To that end, give mobility training serious consideration in your workout routine. Not only will it save you pain, it will allow you to absorb more punishment and do more reps without feeling the effects, which makes you that much harder to bring down.

Hormonal and Adrenal Changes

Another example of physical toughness is harder to see. It consists of the metabolic and hormonal changes that go along with hard training. These can manifest in better energy management, so that you fatigue more slowly, and recover quicker, so that you can come back hard with surprisingly little time to recuperate. When most people would be down for the count, you’re back in the ring, having already caught your breath and cooled off.

The simplest way to train this kind of toughness is by limiting your rest between workouts or exercises, sometimes even at the expense of your performance. Be careful, however: there is a fine line between stimulating adaptation and overtraining, so remember that you need to give your body time and resources to build itself up stronger than before. Eat well and sufficiently, and get enough sleep. These habits will build up a store of resources you can lean on when rest isn’t so easily available. Occasionally, apply an acute stress, like intermittent fasting, to teach your body to adapt quickly and be efficient with energy, or train with little sleep. But in general, you’ll be able to handle more if you’re well-rested and well-fed.

Another interesting technique I’ve recently been using to improve my cardiorespiratory durability is nasal breathing. This involves restricting myself to only breathing through my nostrils, even during hard workouts. The result is more efficient oxygen usage. This technique causes me to regulate my pacing somewhat, but I’ve noticed that I don’t get out of breath nearly as quickly, even when I switch to regular breathing for a particular workout.

Environmental Tolerance

A relatively rare form of physical toughness is environmental tolerance. The most well-known variety is altitude acclimatization, in which athletes train at elevation and compete at sea level. This is normally seen as a way to gain an advantage in sports, but adaptation to low oxygen is also an example of physical durability, the ability to handle a difficult environment.

Another example is cold tolerance. The body will literally increase its ability to generate heat if you habitually go without excessive clothing and expose yourself to acute cold shocks. Even in the winter, it is possible to train with only a t-shirt and shorts. You’ll learn to distinguish between the superficial sensation of cold on your skin and the deep chill that threatens hypothermia. The first gives you feedback about your environment while the second is an indicator of potential danger.

In addition to training with less clothing, I also only take cold showers, which has also improved my ability to tolerate a wider range of temperatures without feeling real discomfort. Of course, both of these are pretty uncomfortable at first, but over time, they become less so, and you will find yourself becoming noticeably more hardy in general.

Physical Toughness Training Summary

- Expose yourself to rough environments and forgo the usual protection, increasing the intensity of exposure slowly over time.

- Learn and implement mobility and self-maintenance exercises into your regular training routine.

- Train with less rest between sets or workouts, but take excellent care of yourself in the meantime.

- Train outside in all weather with as little protection as you can tolerate.

Conclusion

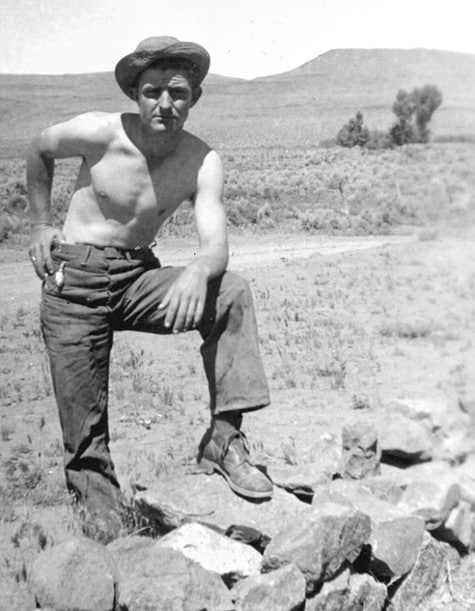

My favorite way to develop pure toughness, both physical and mental — what I call ruggedness — is through outdoor training with minimal protection. Inspired by Erwan Le Corre and the MovNat method of training to approach exercise the same way I approached camping as a kid, I frequently train in a wild environment with nothing on but a pair of shorts, climbing trees, hoisting and throwing rocks, scrambling up and over boulders, and running over gravel-covered trails.

The constantly shifting terrain and objects challenge my body, but they also challenge my patience and focus. When a relatively small rock becomes nearly impossible because of its shape, it is frustrating. When I’m trying to sprint up a hill but keep slipping on loose sand, it is frustrating. When a gnarly tree branch makes pull-ups into a twisted mockery of the pristine movement I rock at the gym, it’s really frustrating. Slight pain from scratches or harsh ground is a constant, and with no clothing, the cold is often an issue, especially if there’s snow.

Everything is harder, or rather, I should say everything is more complex. The result is that I learn how to tolerate stress, both mental and physical, and how to adapt to make something work despite the fact that the environment is not cooperating. I deal with it or fail. When I’m out there, it doesn’t matter that I can deadlift 3x my bodyweight on a bar, because that doesn’t change the fact that a rock is completely off-balance and seems to be actively trying to roll onto my toes. And that doesn’t change the fact that I’m picking it up and carrying it up the mountain anyway.

That is the definition of tough.

______________________________________________

Khaled Allen is a writer and adventurer who explores the ways human potential can be unlocked. He currently lives in Boulder, CO, where is hikes, teaches self-defense, and meditates . . . a lot.

The post You May Be Strong . . . But Are You Tough? appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

0 Commentaires