With our archives now 3,500+ articles deep, we’ve decided to republish a classic piece each Sunday to help our newer readers discover some of the best, evergreen gems from the past. This article was originally published in July 2020.

Undoubtedly, the Civil War was the most consequential event in American history. The fate of the fledgling nation — geographically, culturally, existentially — hung in the balance between the years 1861 and 1865.

Despite its significance, the average American doesn’t possess a very expansive understanding of the conflict. Most of us know a few names — Grant, Lee, Sherman, Jackson; we know Lincoln gave an important speech at Gettysburg; and we know who won the war. But our grasp of everything else is often fairly hazy.

While you could spend your entire lifetime studying the Civil War (over 60,000 books have been written about it!), and go at it from myriad political/social/economic directions, every man should at least have a grasp of the war’s major battles and campaigns.

Over the course of four years and the span of the entire nation (there were important engagements as far west as Arizona and New Mexico), dozens of primary battles and hundreds of other significant engagements took place between the North and the South. Of those numerous engagements, there are nine that arguably had the greatest impact on the outcome of the war, and that you should know the basics on.

While certainly not the entire story of the Civil War, learning about these clashes will give you a broad sense of its ebbs and flows and what ultimately led to the Union’s victory in April 1865.

A Preliminary Note

The first important thing to understand when learning about the Civil War (and martial history in general), and the gruesome numbers associated with its battles, is that “casualties” do not mean “deaths.” A “casualty” is a blanket term for a number of possible outcomes:

- injured — to the point of not being able to fight

- missing — they can’t find a body; many in this category are presumed dead, but it’s not technically proven as such

- captured — many thousands of soldiers on both sides languished and died in military prisons; this number may also include surrendered troops, many of whom were simply sent home without their arms or horses

- dead — while also counted separately, these numbers were part of overall casualty counts as well

Interestingly, fatality numbers from the Civil War keep going up as years go on and historians continue digging into archives and lost graveyards. Less than 10 years ago, the number in fact made a 20% jump from ~620,000 to ~750,000.

To be sure, any casualty is a very bad outcome, especially given the state of Civil War-era medicine, which was a couple decades away from the discovery of germs. These aren’t just glancing blows to the arm; these are injuries where someone is surviving, but perhaps barely, and perhaps not for very long.

It should also be noted that while hundreds of thousands of men died in combat and from combat wounds, scores more — in fact it’s nearly twice as many — perished from disease and accidents. Those numbers are not included in the battle casualty numbers listed below.

9 Civil War Battles Every Man Should Know

Ft. Sumter — April 1861

Location: Charleston harbor in South Carolina

Casualties: 0

Deaths: 0

The opening salvos of the Civil War were shot by Confederate cannons at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861.

In late 1860, in response to Lincoln’s election, Southern states began seceding from the Union, and over the course of the winter and early spring of 1861, the newly-formed Confederacy seized most of the military sites within its boundaries. But a few Southern installations remained under federal control, including Ft. Sumter, an island fort that guarded the entrance to Charleston Harbor in South Carolina. While the fort wasn’t of particular strategic importance, it became a symbolic flashpoint in the mounting tensions between North and South.

Colonel Robert Anderson, who commanded the 85 men protecting the fort, was determined to hold out as long as possible. But as his provisions ran low, the Union had two options, as most of Lincoln’s advisors saw it. It could abandon the fort, and thereby lend legitimacy to the Confederacy’s claim on it, which of course the North wasn’t keen to do. Or, it could resupply the fort with provisions and arms and use it as a launching point for an offensive action. Lincoln didn’t like this plan either, as it would position the North as the aggressor; he wanted the South to start the war so that the U.S. could take the role of defenders of unity. So he came up with a plan to resupply the fort with food and drink only.

Even that was too aggressive for the South; they alerted Col. Anderson that he and his men would be fired upon unless he surrendered. Soon enough the fort’s thick walls were being bombarded by Confederate cannons. For 34 hours, North and South exchanged artillery fire before Col. Anderson was forced to surrender the island. But the North’s objective had been won; the South fired the first shots, even if they were goaded into it.

Nobody died in this initial onslaught, but two Union men were killed afterwards, during the surrender ceremonies, from the accidental explosion of some ammunition. These were the first casualties of the war.

While certainly not a “battle” by definition, the opening shots at Ft. Sumter forever changed our nation’s history.

First Battle of Bull Run — July 1861

Location: South of Washington, D.C., in the Virginia countryside

Casualties: Union: 2,708 | Confederate: 1,982

Deaths: Union: 481 | Confederate: 387

The engagement at Bull Run Creek was the first true battle of the Civil War, taking place more than three months after the first shots were fired at Ft. Sumter. In that intervening time, both armies built up their troops and trained as much as they could. The U.S. standing military was virtually non-existent at this point; state militias were the rule and volunteers had to be rounded up from the individual states. This meant that everyone, on both sides, was very inexperienced. As Lincoln famously said to one of the Union’s brigadier generals, “You are green, it is true, but they are green also. You are all green alike.”

Regardless of their inexperience, Union leaders were confident that this battle would quell the Southern rebellion and put the whole fiasco into the past. Spectators even came from Washington to dot the hillsides surrounding the battlefield, hoping to view a neat and tidy Union rout.

What happened instead was chaos. 36,000 poorly trained soldiers — about 18,000 on each side — collided in a blundering clash. They had no idea what to do, their generals were of little help, and what was supposed to be a small and gentlemanly melee turned into a real and brutal battle. Though a draw in terms of casualties, the fact that the South could actually fight back and hold their own gave them a decisive moral victory. The Union was chafed and sent back to D.C. to lick their wounds, accompanied by the dreadful realization that this was going to be a longer fight than expected.

This was the battle where Thomas Jackson earned the nickname “Stonewall.” He would torment the North for two more years, until Chancellorsville.

Shiloh — April 1862

Location: Southwest Tennessee, just north of the Mississippi border

Casualties: Union: 13,047 | Confederate: 10,699

Deaths: Union: 1,754 | Confederate: 1,728

While blood continued to be shed in skirmishes after Bull Run, there weren’t any major battles in the subsequent nine months. Shiloh — marking the war’s first year almost to the day — was where the war between the states turned to hell and the nation started seeing the shocking casualty numbers that would continue to make headlines for the next three years.

In the early months of 1862, upstart commander Ulysses S. Grant won a series of victories in Tennessee and was working his way south towards Mississippi. Just across the border was the town of Corinth, which was a major rail and supply center. If the Union could take it, they’d control much of the Western theater of the war. Take note: many of these major battles are centered on the control of supply and manufacturing centers.

Before marching ahead with his 40,000 troops, Grant was waiting for reinforcements (another 15,000 soldiers) which he thought would overwhelm confederate general Albert Johnston’s 44,000 troops. Before those backups arrived, however, Johnston launched a surprise attack as day broke on April 6. Union forces retreated a couple miles and suffered heavy losses, but the lines didn’t break entirely — a credit to Grant’s leadership. The next day, the awaited reinforcements arrived, Grant counterattacked, and the Confederates retreated from the battlefield — a clear victory for the Union even though Corinth remained in Confederate hands. Grant’s forces weren’t completely repelled from the region, which allowed him to regroup and start a campaign (a series of battles in service of some larger goal) towards Vicksburg; more on that later.

Despite the victory, the Northern media focused on Grant’s troops being caught unawares on the 6th; it was here that rumors about his drunkenness really began to take hold. His reputation suffered, unfairly, and he would have to work hard to win it back (which he, of course, ultimately did).

At the time, Shiloh was the bloodiest battle that the United States had engaged in — a sad record that would be eclipsed a number of times in the following years. As noted above, this was when casualties and deaths hit the staggering numbers that shocked at the time, but which would quickly become the norm.

Antietam — September 1862

Location: Western Maryland, about 70 miles northwest of Washington, D.C.

Casualties: Union: 12.410 | Confederate: 10,316

Deaths: Union: 2,108 | Confederate: 1,567

September 17, 1862 secured its infamy as the single bloodiest day of fighting in American history when nearly 23,000 casualties were suffered in just 12 hours.

There was a lot at stake for the North going into the fall of 1862. The Confederacy had strung together a number of momentum-building victories and support for Lincoln was flagging. With an upcoming midterm election, his party’s fate was hanging in the balance. He also had the Emancipation Proclamation waiting in the wings, but needed to release it at the right time; to do so when the Confederates had the lead would read as a desperate last move. He was forced to keep waiting and waiting and waiting . . .

Meanwhile, Robert E. Lee was roaming around the northern regions of the Confederacy and trying to figure out when to stage an invasion onto Union soil. That opportunity came near Sharpsburg, Maryland, about 70 miles northwest of Washington, D.C.

Union commander George McClellan had a couple things going for him. The first was a near miracle: two Union privates serendipitously found Lee’s battle plans wrapped around a few cigars and passed them up the chain of command to McClellan. Second, he had twice the number of troops as Lee, though he repeatedly and infamously believed that Lee actually outnumbered him.

Despite these advantages, McClellan faltered in the battle. He didn’t send in all his troops and over the course of a single day, the two sides fought to an intensely violent and bloody stalemate. To his credit, McClellan’s troops did at least force Lee to retreat and therefore end his first foray into Union territory. What ultimately got him canned by Lincoln, though, was that he failed to push after Lee’s retreating forces; leaders in Washington thought that the Army of Northern Virginia could have been vanquished for good had McClellan gone on the offensive at that point.

All that said, the Union did come out on top, if narrowly and at a terrible cost. Lee was pushed out of Northern territory, which was enough for Lincoln to declare a PR victory and release the Emancipation Proclamation.

Gettysburg — July 1863

Location: South-Central Pennsylvania, just across the Maryland border

Casualties: Union: 23,049 | Confederate: 28,063

Deaths: Union: 3,155 | Confederate: 3,903

If you know any battle on this list, it’s Gettysburg. Routinely considered the most important engagement of the entire war, it not only incurred the most casualties but also kept Lee out of the North for good.

Despite the defeat at Antietam the previous fall, Robert E. Lee kept fighting. In December 1862 (an unusual winter battle), he won at Fredericksburg; it was the same story in May 1863 at Chancellorsville (it was there, however, that Stonewall Jackson was killed by friendly fire). After this string of resounding victories — with inferior manpower no less — Lee was again feeling confident in his army and wanted to make another push into Union territory. Another Confederate win would further destabilize Northern support for the war; plenty of folks — called the “Copperheads” — were pushing the federal government to negotiate with the South and restore the broken nation. A victory on Union soil would also signal to the rest of the world, particularly the onlooking British and French governments, that the Confederacy was a government possibly worth backing. The stakes couldn’t have been higher.

So Lee marched his 75,000 men north towards Pennsylvania, followed in hot pursuit by newly appointed Union commander George Meade and his 100,000+ troops. The sheer number of men involved is staggering; the density of bodies on the battlefield is unfathomable compared to our modern concept of battles fought by small strike force teams, drones, and long-distance snipers.

On July 1 the two massive armies entered a three-day crucible characterized by intense and heroic fighting from Union soldiers and egregious tactical errors by Confederate officers. By the end of the day on July 3, nearly 50,000 combined casualties were reported, the most of any battle in U.S. history. On July 4 – Independence Day! — Lee ordered his decimated army to retreat back into Virginia.

In the aftermath — along with Grant’s victory at Vicksburg (coming up next) — foreign governments firmly backed the USA rather than the CSA and the tide of the war turned from the South to the North. General Lee even offered his resignation to Confederate President Jefferson Davis; he was refused, but the damage was already done.

At the dedication of Gettysburg’s National Cemetery in November 1863, Lincoln delivered a brief 272-word address which would go down in history as one of the greatest speeches of all time.

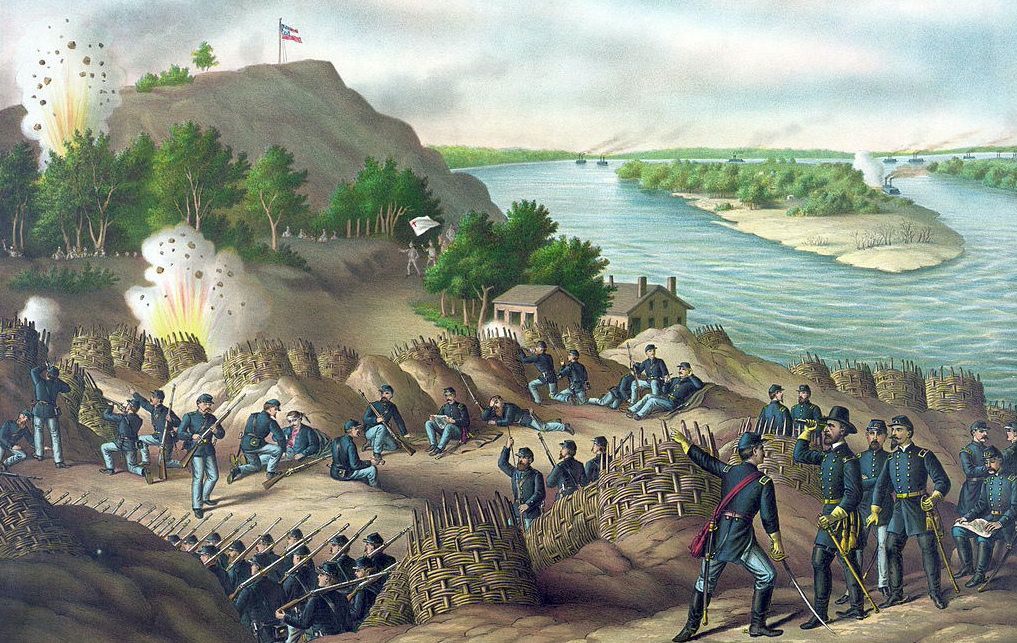

The Siege of Vicksburg — July 1863

Location: Western Mississippi, about 40 miles west of the state capital of Jackson

Casualties: Union: 4,910 | Confederate: 3,202 (another ~29,500 surrendered, which are technically part of most casualty numbers you’ll see for this battle)

Deaths: Union: 806 | Confederate: 805

While Lee was cutting down Union troops in Virginia and marching towards Pennsylvania, Ulysses Grant was slowly but surely working his way towards Vicksburg, Mississippi. The town sat on the bluffs of the Mississippi River; to capture it would effectively cut off that all-important supply line from Confederate use and also separate Texas and Arkansas from the rest of the CSA. Grant originally tried to take Vicksburg after his victory at Shiloh the previous year, but was rebuffed for the winter.

When spring 1863 arrived, he was back at it with a methodical series of marches and battles. In early May, Grant marched his army 180 miles, winning multiple smaller engagements with the help of the impressive Union navy of ironclad war ships. Grant eventually surrounded Vicksburg’s 30,000 troops with his far larger force of 70,000 men. From then on, it was a battle of attrition. For nearly 7 weeks the Southerners held out while the Northerners fought off Confederate rescue attempts. Finally though, in late June and early July, supplies, food, and morale were running low and on July 4 (again!) Confederate Lieutenant General John Pemberton surrendered. The CSA was split in two.

The capture of Vicksburg, and therefore the Mississippi, cemented Grant’s reputation in the North, and more importantly, with Lincoln. Combined with the victory at Gettysburg, things were looking up for the United States of America.

From here, defining battles actually gets a little trickier. As Grant is awarded more of a leadership role, he fully embraces a bulldog philosophy — he meant to keep fighting, pretty much non-stop, until the Confederates either gave up or ran out of men. That said, there are indeed some further important moments and campaigns.

Grant’s Overland Campaign — May-June 1864

Location: Eastern Virginia, roughly between Washington, D.C. and Richmond

Casualties: Union: 54,926 | Confederate: ~33,600

Deaths: Union: 7,621 | Confederate: ~4,206

After Grant was promoted to commander of the entire Union army, it was finally time for him and Lee to clash. After traveling east to Washington, Grant took charge of the maligned Army of the Potomac and immediately took the offensive. The goal was Richmond, capital of the CSA.

With intense fighting at the Wilderness (known as such because of its dense second-growth trees), Spotsylvania, North Anna, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg, the Union actually suffered greater losses than the South. Instead of withdrawing to Washington after each engagement, though, as other Army commanders had done, Grant instead just kept pushing south towards Richmond. He knew the North had more men and greater resources; however cold the reality of the situation was, he was willing to sacrifice men in order to win. His aim was the capture of the Confederate seat of power, and he wasn’t going home until it happened.

The campaign would end at Petersburg, south of Richmond, which was a strategic supply point for the capital and the Confederate army. There at Petersburg, Grant’s army settled in for a 9-month-long battle of attrition (known as the Siege of Petersburg), squeezing the South of its men and resources in a series of relatively smaller battles and engagements. More on how that ended in a bit.

Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign — May-September 1864

Location: From Chattanooga, TN to Atlanta, GA

Casualties: Union: 31,687 | Confederate: 34,979

Deaths: Union: 4,423 | Confederate: 3,044

While Grant was fighting Lee and moving towards Richmond, William Tecumseh Sherman took Grant’s old job as commander of the Union’s Western forces. After the stalemates and heavy losses of men during Grant’s Overland Campaign, Lincoln badly needed a clear Union victory. 1864 was an election year, after all, and the incumbent’s chances weren’t good. The public was sick of seeing the increasingly staggering casualty lists in the newspapers; brokering for peace was preferred to more heavy losses. But Lincoln wouldn’t negotiate and was praying for Sherman to come through.

The general’s aim was Atlanta. After securing Tennessee for the Union at Chattanooga, Northern forces were tasked with marching roughly 100 miles southeast to take the railroad and manufacturing hub of the Deep South. Much like Grant’s Overland Campaign against Lee, Sherman’s forces encountered heavy losses against Confederate generals Joseph Johnston and John Bell Hood. Just as Grant did, Sherman kept attacking regardless of the casualties and forced Johnston’s men, over the course of the sweltering summer months, to retreat and retreat and retreat yet again towards Atlanta. On the night of September 1st, after Sherman had cut off Hood’s supply lines, the Confederate general decided to abandon Atlanta, setting fire to military supplies and installations as he left.

On September 2nd, Union forces marched in, the mayor surrendered, and Sherman sent Lincoln a now-famous telegram: “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.” With those six words, Lincoln’s 1864 election victory was secured; combined with Lee’s inability to fend off Grant in the same time period, the taking of Atlanta spelled doom for the Confederacy.

From there, Sherman would begin his march to the sea and through the Carolinas. Moving hundreds of miles with little resistance, his 60,000+ men pillaged and burned every city and village they encountered, destroying supply lines — and Southern morale — all the way up until the war effectively ended in April 1865.

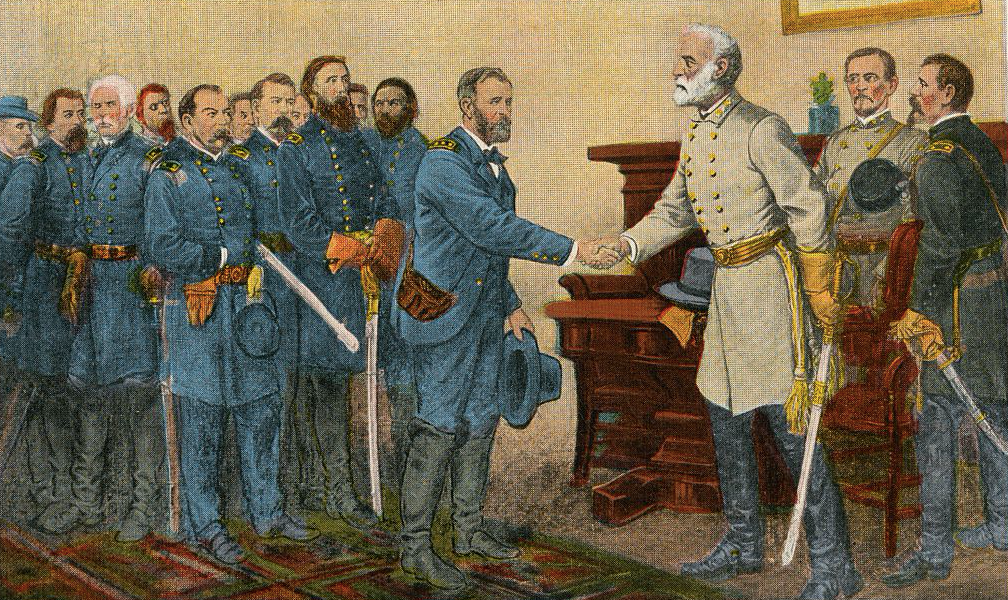

Appomattox — April 1865

Location: Central Virginia

Casualties: Union: 260 | Confederate: 440

Deaths: (there aren’t firm numbers for deaths at Appomattox, but it’s likely a couple dozen or less)

Following the utter defeat in the Deep South, Robert E. Lee’s dwindling army was the Confederacy’s last hope. After holding out for nine long months against Grant’s forces at Petersburg and Richmond, Lee had to retreat, giving up the capital to the Union army. With his band of less than 30,000 men, he moved west into the heart of Virginia, hoping to reconnect with other Confederates in the area. To beat Grant’s 60,000+ army, Lee would need more men.

But the Union cut him off at the small village of Appomattox Court House (the name of the town itself; it was not an actual courthouse). On the morning of April 9th, after a failed last-ditch attack to try to break through the Union line, Lee realized he was extraordinarily outmanned and simply couldn’t continue the fighting.

Later that afternoon, in the parlor of a private home, Lee surrendered ~27,000 men to Ulysses S. Grant. While that single moment didn’t entirely end the war, it triggered the surrender of other Confederate forces, and by June, the bloodiest four years in American history had come to a final end.

The post 9 Civil War Battles Every Man Should Know appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

0 Commentaires