The term burnout was coined a half century ago to describe the exhaustion, cynicism, and feeling of ineffectiveness experienced by those in the caregiving and human-service professions: doctors, police officers, social workers, etc.

Over the decades it has come to be applied to more and more professions and even unpaid work as well: professors are burned out; students are burned out; retail workers are burned out; activists are burned out; parents are burned out. People feel burned out on life, in general.

Yet while the application and discussion of burnout has greatly expanded, what burnout is, exactly, and what causes it has remained stubbornly difficult to pin down.

There is no clinical definition of burnout, no universally agreed upon yardstick for what constitutes it, no official diagnostic checklist as to its symptoms.

In the absence of this consensus, surveys that are administered on the subject each use various kinds of criteria and frame their questions differently, making it hard to accurately assess just how many people are actually experiencing the condition.

As Jonathan Malesic points out in The End of Burnout:

One meta-analysis found that out of 156 studies that used the MBI [Maslach Burnout Inventory — a standard burnout assessment] to examine physician burnout, there were forty-seven different definitions of burnout and at least two dozen definitions each of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and ineffectiveness. It’s no wonder these studies produced widely divergent results, from 0 percent of physicians experiencing burnout, up to 80 percent.

An absence of consensus around burnout also makes it difficult to disentangle it from other conditions that manifest in similar ways. Are you burned out or just bored? When is burnout different from simple tiredness or stress? Is someone burned out, or are they actually depressed?

This murkiness doesn’t mean burnout isn’t real. There’s a reason the term has become so popular: it perfectly describes a common, intuitively understood experience — a state that can feel akin to things like straightforward exhaustion, garden-variety boredom, or clinical depression, but also feels qualitatively distinct. Even if it’s a varied, subjective thing, people often simply know it when they have it. Nonetheless, the murkiness around burnout should invite some epistemological humility into the discussion — a willingness to acknowledge that much about the condition remains a mystery.

That is equally true when dealing with what causes burnout. Because if we don’t have a clear definition of what burnout is, we’re equally confused about what drives it.

Burnout is most commonly associated with overwork. And yet there are folks working 80 hours a week who don’t feel burned out, and people working 30 who do.

Another popular theory is that burnout is a peculiar product of our modern world — something to do with its go-go pace, its atomization, its overstimulation. And yet, even if they did not yet have the word burnout to describe it, people have been complaining of burnout-esque conditions throughout history, especially since the dawn of industrialization. In 19th century America, folks called it “neurasthenia,” and thought it was caused by the rise of stultifying office work and the increasing speed of technological change. Add to this the fact that the strictest of monks, who lived a couldn’t-be-more stripped-down lifestyle almost two thousand years ago, experienced something akin to burnout too, and the idea that burnout is driven by our brain-fragmenting devices begins to seem more tenuous still. (More on those monks in a bit.)

Related to the modernity hypothesis, is the idea that burnout has to do with the increasingly blurry line between our work lives and our personal lives. But that line was arguably even blurrier in past centuries; you woke up, milked the cows, chopped firewood, planted and harvested on your property, mended things around the house . . . farmers were WFH-ing long before we were, with essentially no separation between their “work” lives and their “personal” lives (even explicitly dividing the two would have been a strange distinction to make).

Well, we then think, if burnout isn’t caused by the encroaching reach of modern work, then it is a result of the essential meaninglessness of that work. Modern work isn’t as directly connected to our survival as it was in yesteryear, nor is it always fulfilling on a higher, more philosophical plane either. And yet we have here a problem similar to the overwork hypothesis, in that there are people in jobs that are very meaningful who still burn out, and folks in positions that are devoid of meaning who don’t.

In his book, Malesic postulates that burnout is caused by the gap between our ideals of work and its reality; we expect work to fulfill us on every level, and then are disappointed when it does not. We place too much of our need for meaning on our jobs, and don’t have enough intrinsically valuable pursuits outside of it.

But then we’re back to the inconvenient counterexample of those monks again. They didn’t work for pay, didn’t receive the kind of status-elevating, identity-affirming rewards we seek from our jobs, and their work was entirely pursued for its intrinsic value. So too, one can find plenty of ordinary people who do have other sources of meaning outside the office, and yet still feel burned out nonetheless.

Indeed, perhaps the most peculiar cases of burnout are in those who want to be in the jobs they occupy, who generally like their work, who may be doing meaningful and/or creative things, who aren’t overly-reliant on their jobs to define them, who have a decent level of autonomy, and may even be their own bosses . . . but still experience periods of burnout. There’s no clear, immediate cause of their affliction, no clear answer as to why burnout rears its head when it does — their work hours have not increased, their not-too-onerous workload is about the same, the amount of stress in their job is fairly stable — but they feel burned out all the same. They suddenly feel tired of doing what they’re doing. They hit a wall. They feel like they’ve got to get out. They don’t want to go on with it.

All of this is not to say that overwork, overstimulation, and meaning-bereft jobs aren’t real problems with real, deleterious effects. On both an individual and societal level we should be striving to make work more fulfilling and humane.

It’s just to say that even if we solved all these problems, we would not entirely solve the issue of burnout. Though these issues can make burnout worse, even in their absence, burnout can still occur.

So, if we hope to understand burnout better, we’ll have to look elsewhere for an underlying cause.

Burnout = An Oversaturation of Sameness

No matter your vocation (to include parenting as well), our schedules and tasks are fairly routine and homogeneous. We do the same things, day after day. Even in jobs that involve a high degree of creativity, there is still a sense of doing line work; you’re just spitting out art and media and design instead of widgets. Write an article. Write another one. Write another one. Rinse, wash, repeat. Rinse, wash, repeat. Whether for a 9-5 employee, an entrepreneur, or a freelancer, the conveyor belt of work just keeps on moving.

This problem of sameness has been with us since the dawn of settled, urban civilization. Prior to it, life for hunter-gatherers and farmers followed a rhythmic and cyclical pattern; there were different tasks to accomplish in winter and summer, busier periods and fallow lulls, a time to plant, and a time to reap. There was a seasonality to life, in diet, rituals, work, and otherwise.

Today, we eat the same things, do the same tasks, listen to the same music, and follow the same routines 7 days a week, 365 days a year.

And it may be this sameness that is actually behind our burnout.

It seems to be the case that human beings can only take so much sameness. Our cells get saturated with it and we hit a wall. We don’t want to do the thing we’ve been doing anymore.

If it’s true that burnout is worse than ever in the modern age, it’s because contemporary factors have only exacerbated this trend. Work, the exact same work you do in every season of the year, has seeped into the weekend; few any longer keep what remained one of the last vestiges of our more cyclical lives — the weekly Sabbath. But even if work was corralled back into a Monday-Friday, 9-5 schedule, the sameness problem, though diminished, would still persist.

Indeed, while we can solve the problems of overwork and under-meaning, the problem of sameness has no real solution.

You can, and should, try to reintroduce a little cyclicality into your life — deliberately implementing a bit of seasonality into the foods you eat, the music you listen to, and the events you participate in. Availing oneself of rest and recreation helps too. But even after a long vacation, you’re right back into the relentless loop of regular life. You can mitigate the problem, yes, but you’re then simply at 85% sameness rather than 95%. It’s a balm, but also a drop in the bucket.

The state of life and work in the modern world is what it is. The vast majority of jobs will require us to do pretty much the same things throughout the year, year after year. We can no more introduce a cyclical calendar into our work, than it would have made sense for the farmer to remove the idea of seasons from his.

You can escape from sameness by changing jobs, of course, but it’s impossible to change jobs often enough to both beat burnout and advance in a career: if you stay in a position long enough to accrue professional skill and mastery, you’ll inevitably hit a patch of burnout; if you don’t stay on long enough for burnout to catch you, you’ll never acquire that skill and mastery.

And what if you actively do want to stay in some job, maybe indefinitely? It’s what you want to do, maybe even something you feel called to do?

Is there anywhere we can turn to find an answer for how to deal with sameness-induced burnout?

Let’s get back to those aforementioned monks.

The Monastic Solution to Sameness-Induced Burnout: The Hair of the Dog

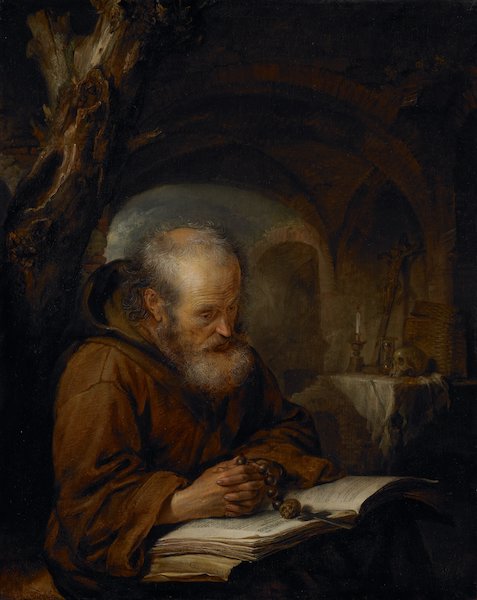

In the 3rd century AD, dedicated Christians from all walks of life withdrew to the Egyptian desert to become hermits and focus their thoughts and energies entirely on God. Known as the “Desert Fathers,” these monks renounced all the creature comforts of civilization to inhabit a tiny, barren, sand-strewn cell and adopt a life of silence, solitude, prayer, study, fasting, meditation, and manual labor.

While monks followed the cycles of liturgy, for the most part their lives were very regimented and routinized; in a way, they were the first to experience the kind of Groundhog Day-esque sameness that would come to characterize the modern age (on a much more austere, ascetic level, of course). So it’s perhaps not surprising that among the challenges they faced, was one that mirrors our modern concept of burnout. The monks called this affliction acedia.

Acedia comes from the Greek for “lack of care,” in the sense of indifference. There is no single English word that serves as a direct equivalent to acedia; the term encompasses a variety of connotations, including exhaustion, languor, listlessness, boredom, disgust, and despair. The condition was marked by a lack of desire to work, and it could affect a monk in both body and mind, creating mental distress and real or imagined physical ailments.

Acedia was also referred to as the “noonday demon,” as it afflicted monks most acutely between the hours of 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., when the hot desert sun sat highest in the sky, and it seemed to these hermits that time stood still and the day would last forever. Evagrius Ponticus, the first monk to really delve into the nature of acedia, considered it the most troublesome and oppressive of all the demons which beset the monastic community.

One of the defining qualities of acedia was a feeling of restlessness, which spurred a monk’s disillusionment with his “co-workers,” an aversion to the endless repetition of his regimented routine, a disgust with the monotony and seeming pointlessness of his work, and, most of all, a desire to abandon his vocation. In these two passages, Evagrius described the effect of acedia on the monk’s mindset:

[acedia] instills in him a dislike for the place and for his state of life itself, for manual labor, and also the idea that love has disappeared from among the brothers and there is no one to console him. And should there be someone during those days who has offended the monk, this too the demon uses to add further to his dislike (of the place). He leads him on to a desire for other places where he can easily find the wherewithal to meet his needs and pursue a trade that is easier and more productive.

—

acedia suggests to you ideas of leaving, the need to change your place and your way of life. He depicts this other life as your salvation and persuades you that if you do not leave, you are lost.

Evagrius observed that the noonday demon offered plenty of reasonable and even altruistic rationales to make the change being suggested: the monk could do more meaningful service elsewhere, could better tend to the family he left back in civilization, and hey, “pleasing the Lord is not a question of being in a particular place; for scripture says the divinity can be worshiped everywhere.”

One of the remedies Evagrius suggested for acedia, and the one he considered most essential, was perseverance. Simply sticking it out. As Evagrius approvingly recounts one monk saying to an acedia-afflicted brother, “Go, eat, drink, and sleep, only do not leave your cell: remember that staying in the cell is what keeps a monk on the right path.”

Suggesting persistence as a cure for restlessness — suggesting sameness as a cure for sameness — may seem counterintuitive, but as Evagrius observed, continuing to act when you don’t feel like acting could break acedia’s hold:

There was a monk who, at the start of the Divine Office [daily prayer], was seized with trembling and fever and a very severe headache. He then said to himself: ‘Now I am sick, and I will no doubt die! Let us arise then before dying and recite the office!’ As soon as he had finished the office, the fever subsided also. And again afterward, by this reasoning, he used to recite the office and triumphed over the thought.

A thought of your own may enter here: “Well, of course monks believed that perseverance was the cure for acedia. Stability is a monastic virtue, and within the context of a church, of a religion, obedience is going to be emphasized and elevated. But the idea of applying this idea to the burnout experienced in secular life — to a vocation one may not feel divinely called to but simply well-suited for — doesn’t make as much sense.”

But, seeing how this hair-of-the-dog cure worked just as well in the life of an artist, can demonstrate how it does.

How Norman Rockwell Cured His Work-Induced Burnout . . . By Continuing to Work

While Norman Rockwell is not always considered a “serious painter” by critics, he certainly took his art seriously himself, laboring intensely, and consistently, at his craft. While his vocation was a creative one, top to bottom, it was also relentless and repetitive. Over a six-decade career, he painted 323 covers for the The Saturday Evening Post, 51 calendars for the Boy Scouts of America, and thousands of illustrations for books, catalogs, posters, and advertisements. He worked seven days a week, and on vacation, almost right up until his death. And for the most part, he loved it. Art was what he felt made to do.

But sometimes, Rockwell would hit a wall. In his autobiography, he describes being hit with a case of burnout which manifested itself in one of the condition’s three main dimensions: ineffectiveness, i.e., a diminished sense of accomplishment, productivity, and capability. (Burnout’s other two mainly agreed upon dimensions, as mentioned at the start, are exhaustion and cynicism):

During the next few months my self-confidence deteriorated rapidly. I began to go out to the studio at all hours to look at my picture and reassure myself that it wasn’t as bad as I’d suddenly remembered it to be. But when I’d get out there I couldn’t tell whether it was good or bad. Or if I decided that it was bad I couldn’t figure out why. I’d rub a head out and repaint it. No, that wasn’t it. I’d change the color of a dress or shirt. No. I’d redraw a hand or eyes, repaint a face, try a different expression. No good, that wasn’t it either. So, worn out, I’d sit there before the easel in the dead silence of early morning, hopelessly confused. And pretty soon, as the birds began to chirp sleepily in the trees along the street and the electric lights faded in the cold blue light of the dawn, I’d take the canvas off the easel and set it against the wall. I’d have to start over. I needed a new model.

But that was just procrastination. It was easier to start the picture over than finish it. I painted one cover four times, using a different model each time, and then burned the canvases and discarded the idea entirely. I couldn’t get a picture to jell in my mind. What I wanted kept eluding me. At breakfast I’d think I finally had it. I could see the completed picture in my mind. Then I’d go out to the studio and, after painting awhile, lose it. Seeing only disconnected details — a hand, a mouth, a shoe. I’d get desperate and begin painting with no purpose, listlessly, filling in a piece here, a corner there, incoherently.

Then one day Billy Sundermeyer, one of my kid models, came into the studio and, seeing the picture on the easel which had been there two months before, said cheerfully, “Boy, you’re through, you’re all washed up!” That scared me. I had to do something, anything, to straighten myself out. My life was going down the drain. All I knew was painting and now that was failing me.

Flailing in his work, Rockwell decided to try the prescription that is often offered for burnout: taking a trip. “Maybe a change of scene would help me,” he thought. But travel didn’t prove an effective remedy, and in fact, seemed to have the very opposite effect:

We put Jerry, our eldest son born in 1932, in a wicker clothesbasket and took the boat for France. But it didn’t do any good. I finished two pictures — wretched illustrations — during the eight months we lived in Paris.

When we arrived home I was in a worse state than before. . . . I tried using new brushes. I experimented with glazes. Not for long, though. I couldn’t stay with anything — a picture, a technique. . . .

Of course I did manage to finish a job now and then. But every one dissatisfied me. And I couldn’t get at the source of my dissatisfaction.

All my stuff is third rate, I thought, down to the last brush stroke. But I don’t know what’s the matter. I’m doing everything just like before.

So how did Rockwell finally emerge from this funk (and the ones that would revisit him throughout his career)? Through perseverance:

I did the only thing I could do. I painted, stuck to the easel like a leech. Whether I liked what I turned out or not. Every morning I went out to the studio at eight o’clock. I worked stubbornly until noon and, after lunch, until five or six o’clock in the evening. I stopped trying to understand why I was confused and dissatisfied. I don’t know what’s wrong, I thought, and I’ll never be able to fathom it. I’ll just paint, because it’s all I’ve ever been able to do.

And in the end, after months of badly painted, out-of-drawing, lackluster covers, done one after another with a sort of dogged despair, I worked myself out of it. My self-confidence returned; I came up with several good ideas; I saw them as coherent pictures all the time I was painting them.

Even now I don’t understand, really, what caused the trouble or how I gradually worked through it. Since then I’ve had other difficult periods. Each time, as I reached the point where I felt I was finished, at the end of my rope, I’ve managed to right myself. Always by simply sticking to it, continuing to work though everything seemed hopeless and I was scared silly.

Keep Calm and Carry On

It bears repeating, underlining, and bolding: if you’re exhausted and unfulfilled in your work, or general situation in life, these issues should be addressed. Chronic stress can create serious mental and physical illness, a life devoid of meaning isn’t worth living, and continuing to work at a job you dislike will not magically make you start liking it. Sometimes there’s nothing to be done but change jobs.

But, while excess and banal work can exacerbate burnout, if sameness is the ultimate root of the condition, and sameness is endemic in modern working life, it’s possible to experience burnout in a job that you generally like, feel well-suited for, and actually want to stay in.

In such a case, the first thing to do when hit with burnout is not to freak out. You’ve hit a wall. You feel restless. You’re tired of the work. You feel like you need a change. OK. When you feel this way, it’s natural to assume that something is “wrong.”

And it’s possible you do indeed need to make a big change.

But it’s also possible that you’re just hitting a sameness saturation point, which arrives on a mysterious and seemingly random schedule. You may think you’ll be happier in some other, cooler career, but you’ll assuredly experience times of burnout there, too. Even NBA players say that amidst their 82-game season, there are times when a game’s opening hype-up music doesn’t at all match their mood; they’re decidedly not excited about running out on the court to play, feel totally tired of the routine, and think, for the dozenth time, about maybe retiring. Even a basketball game can feel like a widget.

As bloggers/podcasters, we ourselves work at what are seemingly considered desirable jobs. While this work is definitely autonomous and creative, it’s also surprisingly relentless and repetitive, with long, unending hours. We each respectively work 50-60 hours a week (divided between the school day and the evenings, so we’re not neglecting our kids), every week and every weekend, and haven’t had a non-working vacation in almost fifteen years. As soon as one podcast or article is done, it’s time to start working on the next. For the most part, that’s totally fine — the bulk of our work is interesting and fulfilling and enjoyable. Yet we each occasionally hit a wall where we’re sure we can’t go on with it anymore, and consider starting over in some dramatically different career. At such times, because we love our work overall, we simply choose to keep going. The feelings of burnout inevitably dissipate just as mysteriously as they arrived, and we’re back to really enjoying our jobs again.

It would be a mistake to stay in a job you find soul-sucking. But it would also be a mistake to abandon something you were meant to do, something that’s your thing, something that fits you well, something that may be the best spot for you in life, because of a rough patch that is normal, inevitable, and ultimately passing.

The Desert Fathers thought that one of the cleverest tactics of the noonday demon was to keep the afflicted from being aware they were suffering from it. The monk would then assume that his restlessness, tiredness, and disgust for his work meant he was laboring in the wrong vocation. But experiencing acedia, or burnout, could just mean you’ve arrived at a temporary sticking point, that, if pushed through, will evaporate under a sun that will not always blaze so hotly. Revealing acedia for what it is, pulling off its panic-inducing mask, the Desert Fathers said, was the first step to its dissolution; as Evagrius put it: “as soon as a man has recognized it, it is calmed.”

The post A Counterintuitive Cure for Burnout appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

0 Commentaires