To use leisure intelligently and profitably is a final test of a civilization. — Jay B. Nash, Philosophy of Recreation and Leisure

For thousands of years, man largely got the doses of challenge, creativity, achievement, and satisfaction needed for psychic health from his work. Initially his work in hunting and gathering was directly connected to his survival; then as civilization, and in turn trade and commerce, began to expand, he remained connected to the final product of his labors.

But after the dawn of industrialization, work became increasingly routinized, mechanized, and bureaucratized. Work was fragmented and more and more layers developed between a man’s labor, and its results, fruits, and outcomes.

After a day of work in the present age, many individuals cannot discern that the world is any different for their effort, and they themselves do not feel any different as a result of it.

The more man is alienated from his work, the more he must look elsewhere for sources of growth, mastery, and fulfillment; the more he is alienated from his work, the more critical it becomes for him to cultivate his life outside of it — his leisure.

The Critical Importance of Well-Used Leisure Time to the Individual, and to Society

Recreation [can] take on significance—possibly spiritual significance. Recreation can and even may become a way of life.

In 1953’s Philosophy of Recreation and Leisure, Dr. Jay B. Nash, professor of physical education, health, and recreation, argues that in a world where work is increasingly unsatisfying, leisure takes on an outsized importance; the way it is used can either exacerbate the malaise created by the shrinking significance of work, or act as a critical counterbalance to it.

In the former case, the dynamic runs something like this: people feel tired from their work, and interpret this tiredness as mental/physical fatigue caused by over-effort; they then seek rest in the form of mindless, passive amusements; these amusements, however, while they offer a temporary distraction in the short-term, leave people feeling more enervated in the long-term; this makes them seek more passive entertainments to feel better; and on the cycle goes. In this way, leisure time only deepens the malaise that can lead to garden-variety unhappiness, as well as contribute to clinical cases of depression and anxiety. It’s a cycle, Nash observed, that leads modern individuals to “go to pieces.”

If, on the other hand, as is often the case, the seeming fatigue caused by work is not the result of too much engagement, but too little of it — is in fact a manifestation of boredom — then leisure, used wisely, can act as the reinvigorating antidote to the modern tendency towards psychic disintegration.

Leisure, Nash says, can supply the interest, stimulation, and sense of accomplishment that is often lacking in paid work, would otherwise go missing from our lives, and is ultimately critical to psychological wholeness and the integration of character.

Nash argues that it is “in the practice of skills” — real, concrete, progressively-developed skills that contrast with the typically abstract energies we moderns typically deal in — that man achieves what he calls “all-thereness.”

Indeed, he says that man possesses a “skill hunger” that must be fed if he is to thrive.

The concept of the greatest number of skills for the greatest number of people is probably the best foundation for a democratic society. Greater skills mean greater eagerness for life and this in turn develops a joy of living. The true vocation of man in the universe is to exercise skill in one or another of its innumerable varieties.

Nash further argues that active, creative recreation is not only critical to preserving the wholeness of the individual, it is critical in preserving the health of a democracy. Not only because a democracy has an interest in ensuring its citizens are psychologically sound, but because leisure pursuits can develop the kind of patience, critical thinking, and engaged orientations that are needed to facilitate a functioning political life.

The death stage of a civilization is often marked by the rise of what Nash called “spectatoritis” — an epidemic retreat into predominantly passive amusements. Think of the Romans and their gladiatorial games. When a people is satisfied with the pseudo sustenance of bread and circuses, it no longer recognizes the cultural and political decay happening around them, and is too surfeited by superficial entertainments to muster the will to do anything about the rot.

The Wise Use of Leisure Does Not Happen Naturally

We are learning that the profitable use of leisure is an art in itself and not something that comes automatically.

There are myriads of books and podcasts and courses about how to manage your work time and be more productive.

But there is comparatively little discussion of what to do with your free time.

This is partly because we like to think of our leisure time as something freeform that should be utilized spontaneously. And certainly, much of the joy of our leisure is that it is ours, with no set rules, structures, or expectations. We figure we’ll simply know how to use our free time as it arises.

When, as it so commonly happens, our evenings and weekends pass by in an indistinct, underutilized, unsatisfying blur, we figure the problem isn’t caused by an untrained instinct, but a lack of time. If we had a little more of the latter, we think, we’d have put our leisure to better use.

Yet the data belies this belief.

If it were the case that the more leisure time we possessed, the more we’d use it for creative, constructive activities — socializing, reading, exercising, playing sports, engaging in hobbies, and so on — then, quite obviously, the more that leisure time increased, the more that participation in such activities would increase.

And yet the very opposite has happened.

In the midst of a typical workweek grind, it can seem like we’re the busiest and most labor-laden humans that have ever existed, and it’s easy to forget just how dramatically work hours have fallen over the past 150 years. As researchers have pointed out, the amount we toil has been cut in half, meaning that “Before this revolution in working hours people worked as many hours between January and July as we work today in an entire year.” Just between 2019 and 2020, people gained another half hour of leisure time (partly due to an uptick in the number of folks who started working from home and got to drop their commute — a situation that for many will remain permanent, even post-pandemic).

As work hours have fallen, time spent watching television/videos/movies and playing video games has risen, so that those activities now occupy almost four hours a day (and that doesn’t even account for random phone scrolling/checking), dwarfing the time spent on every other leisure activity, and making up almost 75% of the 5.5 hours of leisure time people have, on average, at their disposal each day.

Thus, while we often imagine ourselves as would-be artists, craftsmen, and hobbyists, who are only thwarted in taking up more meaningful leisure pursuits by a scarcity of time, our societal track record undercuts this kind of self-flattering optimism.

If we’re honest, the more free time we get, the more we tend to struggle with figuring out what to do with ourselves. All humans tend to default to the path of least resistance, and towards lowest-common-denominator activities. Breaking that passive pattern, in order to make better use of our leisure time, requires some deliberate direction and active intention.

The Pyramid of Leisure

Who was the happy man? He painted a picture; he sang a song; he modeled in clay; he danced to a call; he watched for the birds; he studied the stars; he sought a rare stamp; he sank a long putt; he landed a bass; he built a cabin; he cooked outdoors; he read a good book; he saw a great play; he worked on a lathe; he raised pigeons; he made a rock garden; he canned peaches; he climbed into caves; he dug in the desert; he went down to Rio; he want to Iran; he visited friends; he learned with his son; he romped with his grandchild; he taught youth to shoot straight; he taught them to tell the truth; he read the Koran; he learned from Confucius; he practiced the teachings of Jesus; he dreamed of northern lights, sagebrush, rushing rivers, and snow-capped peaks; he was a trooper; he had a hundred things yet to do when the last call came.

While the specific ways someone chooses to use his leisure time should be individual and idiosyncratic, some guiding principles are helpful in thinking about how to make the most of it.

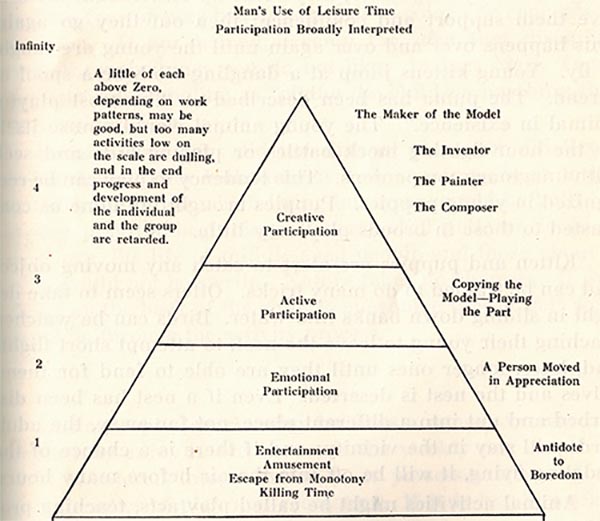

Nash offers these guiding principles in the form of a pyramid.

At the base of the pyramid sit society’s most passive amusements; as you ascend the pyramid, activities become increasingly participatory and creative, and increasingly beneficial to the human soul.

Let’s talk about each level of the pyramid, starting from the bottom, and working our way up:

Spectatoritis-Type

As we’ll see when we move to the next level on the pyramid — Emotional Participation — watching, listening, and reading aren’t necessarily passive activities, and aren’t necessarily consigned to the pyramid’s bottom layer. But these activities do fall into the Spectatoritis category when they fail to engage one’s thoughts and emotions. These are the most mindless entertainments — the kind of thing you do when you want to mentally check out from life: watching a dumb sitcom or an action flick you’ve already seen a million times; scrolling through Instagram or TikTok; scanning headlines on a tabloid-y news site; listening to Top 40 radio; spectating at a sports game (sometimes).

Passive amusements, what Nash calls “looking on,” aren’t entirely without merit. They can provide an easy distraction, a chance to turn off the old brain. But they’re like junk food in a diet; okay as an occasional indulgence, but detrimental when overindulged in.

Passive amusements, Nash said, are of the going-nowhere, “Merry-go-round type where the rider gets off just where he got on.” Scrolling reddit and watching TV will leave you essentially unchanged; spend a weekend merely “looking on,” and you go into Monday morning the very same person who headed into Friday night.

Emotional Participation

Reading, watching, and listening can become participatory rather than passive, Nash says, when “You have looked on but you feel a part of it.” A good book, meaningful film, thoughtful television show, beautiful art exhibit, or teleporting music performance, as well as some sporting events, can stimulate your thoughts and/or touch your emotions; the event/media reaches into you, and you reach into it; you are involved in it. Such experiences can expand your perspective, clarify your vision, provoke some insight.

One characteristic of good as applied to an activity must be whether or not it carries one onto new activities. Does the activity open up new realms, new worlds, new interests? Does an activity branch and broaden out to touch several phases of life?

The gauge of whether or not an activity is emotionally participatory rests most of all on whether it spurs you to do something: to be different, to try a new task, to learn more, to take action. Such activities point beyond themselves to new philosophical and recreational horizons. As Nash puts it, such activities “have a catalytic power to set up . . . chain reactions of new experiences.”

Active Participation

As one ascends above the two levels of spectator-type activities, he moves out of the stands and into the arena. He not only brings his eyes and ears and feelings to an activity, but involves his whole self.

At the level of Active Participation, an individual participates in an activity in which the model/pattern/system has been created by someone else; he acts in a play, performs a song, plays a game or sport, hikes a trail, cooks a recipe, and so on. As the name of this level of leisure implies, he not only feels moved to action, he follows through on that prompting.

Creative Participation

When an individual moves beyond following a model created by someone else, and creates his own model, he has reached the pinnacle of the pyramid: Creative Participation. Even when his works are for amateur use and private display, or he simply rearranges preexisting elements, if he crafts something in a novel way, does something a little differently than it’s ever been done before, he engages in the act of creation. This is man as composer, poet, artist, playwright, photographer, author, chef, filmmaker. This can also be man as social or recreational organizer — he who throws a party, hosts an event, or creates a new club, fraternity, sport, challenge, or tradition.

Nash advised people to spend as much of their leisure time as possible in activities represented by the pyramid’s top three levels — and the higher one could reach, the better. Doing so, he counseled, would provide a counterbalance to the atrophying effects of unchallenging and unstimulating work, scratch one’s “urge to do,” and forge a path to greater fulfillment.

Not only do we, on average, work less than any post-industrialization people, work hours seem poised to decrease even further in the future, and there is talk of a move to a four-day workweek. While such predictions have in fact been posited for more than a century now, the viability of their coming to pass seems greater than ever before.

If our work time is indeed destined to decline further, while our leisure time rises, the use we make of the latter will only increase in importance. Will we be content to sit in the literal and metaphorical grandstands and theater seats, looking on at life, and letting our social, moral, cognitive, and physical capacities atrophy? Or will we be full participants in life — doers rather than viewers, creators rather than consumers — and engage in the skill-developing, body-strengthening, mind-expanding activities that will build us into joyful, well-rounded individuals? The stakes are real; as Nash observes, “In time, the whole character of society will be determined by the way in which the mass of citizens spend their leisure.”

The post The Pyramid of Leisure appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

0 Commentaires