With our archives now 3,500+ articles deep, we’ve decided to republish a classic piece each Sunday to help our newer readers discover some of the best, evergreen gems from the past. This article was originally published in May 2016.

Have you ever had someone come to you crying?

Maybe your wife had a brutal day at work and fell apart when she came through the door.

Or your mom lost it while reminiscing about your deceased dad.

Or your usually stoic buddy broke down about his girlfriend dumping him.

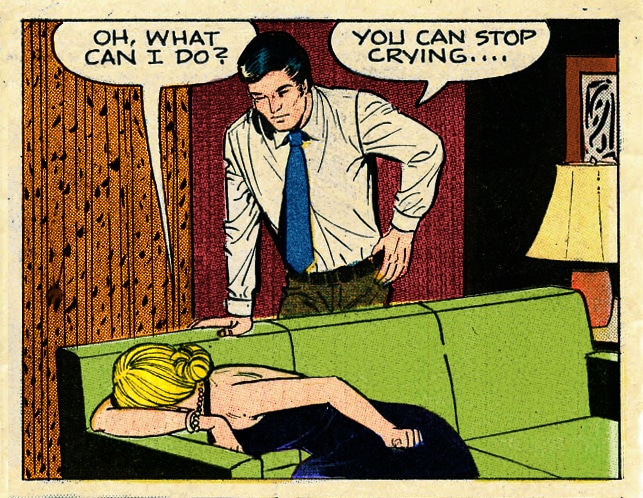

Interacting with someone who’s sad and hurting can be awkward; you want to be there for them, show your empathy, and strengthen your relationship, but it’s hard to know how to act and what to say. A lot of us end up sitting there uncomfortably, offering some awkward back pats, while saying, “There, there, it’s okay.”

I know a lot of guys out there struggle with this scenario, because I’ve gotten more requests to cover this topic than any other.

I held off on doing so, because while I thought I did a pretty good job in this area myself, I wanted to see if there was real research out there concerning best practices. Fortunately, I recently came across some great tips from Dr. John Gottman, a professor of psychology and arguably the foremost relationship expert in the country. Today I’ll share his advice, as well as the tips I’ve gleaned from personal experience, on how to comfort someone who’s sad, so you can help them in their time of need and be a better son, friend, and husband/boyfriend.

How to Comfort Someone Who’s Sad/Crying

“Witness” their feelings. One of the most difficult things about trying to comfort someone who’s hurting is feeling like you don’t know what to say. Fortunately, most of the time people aren’t actually looking for you to offer specific advice or pearls of wisdom; the most comforting thing in the world isn’t an inspiring platitude, but feeling like someone else gets what you’re going through, and that you’re not alone in the world. The thing people want most when they’re hurting is for you to act as a sounding board and to show understanding and empathy. Gottman calls this “witnessing” your loved one’s distress.

So to start off comforting someone, simply describe what you’re seeing/sensing. Say something like, “I know you’re having such a hard time with this,” or “I’m sorry you’re hurting so much.”

Also affirm that you hear what they’re saying by saying it back to them in your own words.

So if your wife, who’s in tears, says:

“My boss told me I wasn’t cut out for my job, and that if I make one more mistake he’s going to fire me.”

You would say back:

“It sounds like you’re upset because you haven’t been doing as well as you’d like at work, and you’re worried that you’re going to lose your job. Is that right?”

Affirm that their feelings make sense. You want to not only acknowledge that you hear the person’s feelings, but that they make sense to you. It’s lonely to feel like you’re coming at something from out of left field.

So you might say to your friend who’s going through a bad break-up: “Of course you’re devastated. I honestly was depressed for months after Emily and I ended things.”

Keep in mind that while sharing your similar experiences shows empathy, you want to be careful not to pivot the focus of the conversation onto you. Don’t try to one-up the person by sharing a story of how you’ve had it worse, and don’t go on and on about your own experience. Instead, briefly share how you’ve been through something similar, and then return the focus to the other person by asking them questions and eliciting more details (see the next point). Even if you haven’t experienced the same thing, you can still say, “That’s never happened to me, but I can really get why you’re feeling that way.”

If the person’s feelings don’t make sense to you, that makes the next step all the more important.

Show the person you understand their feelings, and facilitate the deepening of his or her own understanding of them. Sometimes people do want advice or a proposed solution to their problem, but even then, they usually first simply want to vent their feelings; as has often been observed, this is especially true of women. So hold off on going into problem-solving mode at first, and just listen. See your job not as talking, but as getting the other person to talk, so that they can sort through their feelings themselves; they may not even be able to articulate why they’re feeling down, unless you draw it out of them.

In getting your friend/partner/relative to open up, you demonstrate your genuine support and interest, enhance your understanding of their suffering, and let them know that you know why they’re sad; as the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard (he the advocate for indirect communication) advises, that last part is important even if you think you already understand, and already know how to solve their problem:

“If real success is to attend the effort to bring another person to a definite position, one must first of all take the pains to find that person where he or she is and begin there. This is the secret of the art of helping others. Anyone who has not mastered this is himself deluded when he proposes to help others. In order to help another effectively, I must understand more than he — yet first of all surely I must understand what he understands. If I do not know that, my greater understanding will be of no help to him. If, however, I am disposed to plume myself on my greater understanding, it is because I am vain or proud, so that at the bottom, instead of benefiting him, I want to be admired . . . To help does not mean to be a sovereign but a servant . . . not to be ambitious but to be patient.”

Or as the minister Fred B. Craddock puts it so well:

“To understand what is understood and how it is understood means not only that you understand but that the listener understands that you do.”

To facilitate this drawing out process, Gottman recommends using “exploratory statements and open-ended questions” like:

- Tell me what happened.

- Tell me everything that’s bothering/worrying you.

- Tell me all of your concerns.

- Tell me everything that’s led up to this.

- Help me understand more about what you’re feeling.

- What set off these feelings?

- What’s the thing that’s worrying you the most?

- What’s the worst that could happen? (If you feel like someone is catastrophizing — believing something is much worse than it is — try working through this exercise with them)

Gottman recommends against asking any “why” questions since, no matter how well-intended, they tend to come off as criticism:

“When you ask, ‘Why do you think like that?’ the other person is likely to hear, ‘Stop thinking that, you’re wrong!’ A more successful approach would be, ‘What leads you to think that?’ or, ‘Help me understand how you decided that.’”

By working through these exploratory statements and questions, you’ll hopefully not only get a better understanding of the person’s suffering, but help them come to understand it better themselves too. They may come up with their own solution, realize that things really aren’t so bad, or simply feel better having gotten their worries or grief off their chest.

Don’t minimize their pain or try to cheer them up. When faced with tears, it’s natural to want to try to snap the person out of it with smiles and jokes, or by insisting that whatever they’re upset about is “no big deal.” But someone who’s upset wants to take you on a tour of their melancholic landscape, pointing out the blue-tinged landmarks they’re seeing; it doesn’t help to say, “Nope, there’s nothing out there!” or “Look, there’s a dog riding a unicycle!” Something may not feel like a big deal to you, but it does feel like a big deal to them. Don’t trivialize their experience, but walk through it with them.

But what if someone’s reason for feeling sad really is no big deal? If you don’t think their deprecating feelings about an event, or themselves, are justified, ask, “Can you think of any evidence that’s contrary to the conclusion you’ve reached?” If they can’t, ask if you can suggest your own and share an alternative way of seeing things (it’s nice to ask permission here, because offering a contrarian view, unsolicited, tends to come off as critical and antagonistic).

If someone’s feelings are habitually irrational and grossly disproportionate to their cause, or they’re constant complainers who get upset about everything, that’s probably someone you simply want to minimize contact with if possible.

Offer physical affection if appropriate. Sometimes people don’t want to talk, and don’t want you to talk either — they just want to be held in silence. But one of the things I think guys struggle with when trying to comfort someone is knowing how much physical affection to offer. The gestures you make should generally match whatever you give the person on a normal basis. If you’ve never hugged the person you’re comforting, then don’t go beyond putting a hand on their shoulder, or an arm around it. If they’re someone you hug regularly, then give them an embrace. If you’re intimate partners, offer a snuggle.

Now this just goes for gestures you initiate; in gauging the level of needed physical affection, you should really let the other person take the lead — they may lean in to that arm you drape over their shoulder, and if they do, you should reciprocate.

Just be careful about the messages you send; if a girl is crying because you’re breaking up with her, or she just confessed feelings that aren’t requited, physical affection could send a mixed message. Also, if you make your affection towards your significant other too sensual, rather than comforting, they could be offended that you’re trying to make a play for sex, when they’re trying to work through a tough issue.

Suggest action steps. As mentioned above, there are times when people just want to be heard and comforted, and don’t want a solution to their feelings of sadness (often there is no solution; you can’t bring your dead dad back — grief is just grief). In such cases, after going through the above steps, the person typically feels better for having shared the burden on their heart, and the sadness runs its course. Ask if there’s anything else they want to tell you. If it’s nighttime, when these feelings tend to come out, suggest they go to bed; everyone feels better in the morning.

Other times, the upset person still feels unresolved, and wants advice on what to do. First, ask them if they have any ideas as to steps they could take to improve the situation — solutions are more likely to be adopted if the person comes up with them on their own. If they’ve got big, macro ideas, help break those down into next-action steps. If they’re at a loss as to how to proceed, offer your suggestions.

With someone who’s sad not because of an isolated event, but because they suffer from depression, pivot as quickly as possible to talking about an action step, or just inviting them to do something else besides talking — e.g., take a walk or go for a drive together. Excess rumination is not only ineffective in alleviating depressed feelings, it can actually make them worse.

Affirm your support and commitment. As a comfort-driven conversation winds down, let the person know that you understand what they’re going through, that you’re sorry they’re going through it, and that your shoulder is always available for crying on.

The post How to Comfort Someone Who’s Sad/Crying appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

0 Commentaires