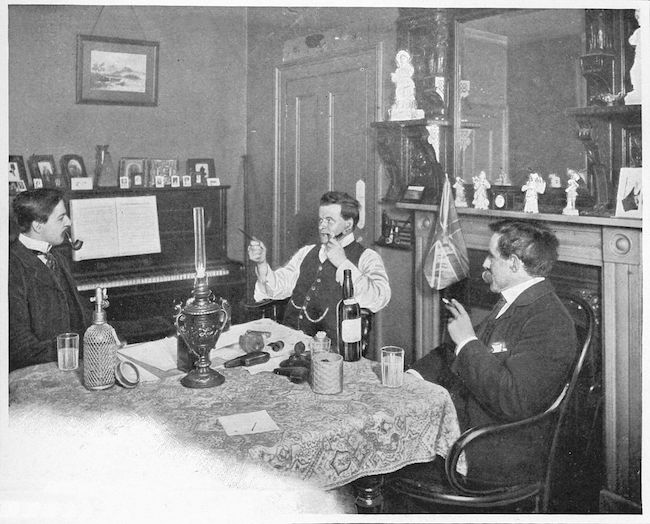

Much has been made of the increasing number of Americans living alone (in 1960, single-person households constituted 13% of all households; today, they represent 28% of them). But such a period is not without historical precedent. While 51% of men ages 18-29 are single today, in 1890, 67% of men in roughly the same age bracket were. In the late 19th century, socio-economic forces led men to postpone marriage, and an entire bachelor sub-culture developed; in cities, bachelors often congregated together in “Bachelor Districts,” formed clubs, and hung out in billiard halls, saloons, and barbershops. The period between the Civil War and World War I ultimately spurred new industries, shaped America’s conception of masculinity in the 20th century, and became known as “The Golden Age of the American Bachelor.”

Most bachelors of this period lived with their families, but many lived on their own in boarding houses and apartments. In 1906, A. Lyman Phillips wrote A Bachelor’s Cupboard: Containing Crumbs Culled from the Cupboards of the Great Unwedded, a book that sought to help these stags set up an independent, and flourishing, life. The book contains chapters on how to live on a budget, furnish one’s quarters, stock a kitchen (tabasco sauce was considered “indispensable”), cook a variety of dishes (both while staying at home and camping in the wilds), mix drinks, dress appropriately, do housekeeping, entertain guests, and generally be a skilled host and suave, competent gent. Lyman paints bachelorhood not as some default state in which a man bides time before marriage, or as an excuse to resort to lowest-common-denominator living, but as a role to be celebrated and improved upon. He offers an ideal of the bachelor as a man who betters his own life, and in turn betters the lives of others.

A single male of the present age might not be nostalgic for a time in which you had to have a chaperone present when entertaining a lady friend, but he might look back wistfully on a period when bachelors were often invited to eat at other people’s homes three or four times a week and could be “persistently certain that he is welcome everywhere, and that when he lunches or dines at a house he confers a favor.” Perhaps if the modern bachelor were as charming a figure as Lyman lays out, he would be similarly in demand.

What follows is the first chapter of A Bachelor’s Cupboard. You can read the rest for free here.

________________________________________________________________________

Being a bachelor is easy. Staying a bachelor-ah! there’s the hitch! But that’s another story. Yes, it’s easy to be a bachelor, but to be a thoroughbred, unless it is inbred and the single man is “to the manner born,” is more difficult. It requires unlimited time, patience, and education as well as a store of myriad bits of information on a multitude of subjects.

The “correct” bachelor must not only know how, but he must know why. He must be a woman’s man and a man’s man, an all-round “good fellow.” He must “fit” everywhere and adapt himself to all sorts of society under all sorts of circumstances. Good breeding and kindliness of heart are the essentials. These, above everything, he must have; and given them, the other attributes may be easily acquired by study and observation.

Any man may be a bachelor—most men are at some time in their lives. The day of the “dude” has passed and the weakling is relegated to his rightful sphere in short order. But to the bachelor the world looks for its enjoyment and inspiration and gayety. Upon him, as a matter of course, fall many burdens. These, if he knows how to bear them, are speedily transformed into blessings and counted as privileges.

Have not some of the world’s greatest men enjoyed lives of single-blessedness? Have not some of its greatest bon-vivants, epicures, artists, musicians, and writers led the solitary life from preference rather than necessity?

“I am a bachelor,” says one gallant, “because I love all womankind so well I cannot discriminate in favor of the one.”

Bachelors are the most charming of entertainers. What woman ever refuses an opportunity to chaperon at a bachelor dinner or studio tea? What débutante does not feel secretly ecstatic at the very idea of looking behind the scenes and peeping into the corners of some famous bachelor ménage? And who, indeed, can be a more perfect host than a bachelor? He can be equally gracious and devoted to all women because of the absence of that feminine proprietorship which always tends to make the married man withhold his most graceful compliments, his most tender glances, and his most winning smile.

It is the bachelor who makes society; without him it would indeed be tame and find itself dwindling down into a hot-bed of discontent, satiety, and monotony. He adds just the right touch of piquancy to its hothouse existence and furnishes husbands for its débutantes and flirtations for its married women.

His versatility makes him a valuable acquisition to any gathering. He knows the correct thing in dress, the latest novelty of the London haberdasher, and what the King is wearing to Ascot. He is familiar with the etiquette of European courts and American drawing rooms and can tell of the little peculiarities of social functions in Washington, Boston, Baltimore, Charleston, London, or Vienna.

He can quote that prince of epicures, Brillat-Savarin, and tell how Billy Soule broils trout over the coals. When it comes to condiments, he can tell by the aroma of a dish what its seasoning is; at mixing toothsome devils and curries he is a past master. He is an authority on wines and knows how to judge them; or, possibly eschewing alcoholic beverages, he can offer satisfactory substitutes that fill the bill, and is sufficiently broad to take his lime and seltzer or Apollinaris with a crowd of good fellows growing mellow over their champagne; and ten to one he has a fund of witty repartee that scintillates among that of his fellows. If he drinks, he does it like a gentleman and knows when to “turn down the empty glass.” If he has a hobby, he rides it decently without coming a cropper at every high gate.

The correct bachelor knows all these things intuitively. He may be impecunious, but he must be artistic. The “artistic temperament” is more easily acquired than the stolid young lawyer poring over his Blackstone may dream. The combination of the practical and artistic is much to be desired, and with each succeeding generation this is becoming more largely a matter of intuition and environment than study.

The artistic temperament flourishes in that real Land of Bohemia “where many are called, but few are chosen.” There “every man is manly, every woman is pure” and the spirit of bon camaraderie is always in the air. The old Greek maxim, “Know thyself,” and that other, “To thine own self be true,” build a creed of greater worth than tomes of ancient lore. “The hand clasp firm of those who dare and do—half way meets that of those who bravely do and dare.”

The “men who do things,” the most talked-of bachelors, form brilliant coteries in different parts of the world. The Lambs’ Club in New York, the Bohemian Club in San Francisco, bravely pulling itself together after its great disaster, the Savage Club in London, the St. Botolph Club in Boston—all show in a glance over their membership rolls the names of men who not only do things, but do them well. Renowned artists, famous composers, maestros, millionaires, authors, and all-round good fellows gather to applaud the work of their fellow members and are eager to enjoy the spirit of Bohemian brotherhood.

Many bachelors, after an early life of uncertainty, find themselves past the threshold of success, but through money and character they may attain a place in society.

Many have slaved over ledgers and bent over the ticker, who have had no time in the bustle and worry of their business life and struggle for success to gather the odd bits of miscellaneous knowledge of etiquette, arts and letters, epicurism, habiliment, and so on, that are required of a successful bachelor. “Being a bachelor” becomes a business, even as keeping a set of books or making investments. Any bit of knowledge that will add to his accomplishments is as good a business investment as a bond or mining certificate. The latter may be taken away, but his knowledge, once gained, is always his “to have and to hold.”

Even as a little knowledge is a dangerous thing,” how much more dangerous is it to be without it. No one is so wise that his wisdom may not be increased. One bachelor may be able to win at poker or break a broncho into quivering submission to his will, but will be quite out of place, like the proverbial bull in a china shop, in a fashionable drawing-room, and all for want of a little knowledge of the etiquette of afternoon teas or evening receptions. Another may be able to cook and serve a French dinner of eight courses, but be pitifully wanting in the lore of camp cookery and “roughing it.”

For some years the world at large has been possessed of a passion for knowing “how to do things.” “How to do this” and “how to make that” have been “topliners” in Sunday newspapers, and from “Jiu Jitsu in twenty lessons” to “what to name the baby” and “how to make your canary bird sing,” these expert writers have condensed their stores of knowledge into printed page or paragraph and have set forth in concise or exhaustive information, as the case may be, “how to do” almost everything under the sun. Even David Belasco has been tempted into telling how to write plays, and Bernard Shaw instructs one upon “going to church.” “Bossie” Mulhall shows how to rope a steer and Theodore Roosevelt tells how to lead a strenuous life; but in all this great store of condensed instruction one field at least has remained still uncovered. No one has written on “how to be a bachelor,” for the spinsters seem to have appropriated all the space. For them there has been advice a-plenty on how to select a husband and how to keep on the sunny side of thirty, and so on through the gamut of womanlore.

Why has the bachelor been neglected? Possibly because he is popularly supposed to be quite self-sufficient and omniscient. An occasional paragraph on why clocked socks are better form than embroidered ones, or how to tell when the girl of one’s choice loves him, creeps into print; but for the bachelor who really wants to “know how” there is no royal road to learning save the rocky, steep thoroughfare that each one must needs climb by himself on his daily journey in quest of Experience.

There is no “complete compendium” for the ambitious bachelor who wishes to become bon vivant, epicure, “connoisseur de vins” and “up” on all the little things that combine to make him an authority on the things of single men of the world. But his proverbial fare of “bread and cheese and kisses” needs to be modified to suit present-day needs, and the judicious addition of a few crumbs to his store of provender may be welcome. From these crumbs from many bachelor cupboards, then, may he find an occasional “crumb of comfort” and a little lift over some hard place along the road. If he finds it herein, the purpose of “A Bachelor’s Cupboard” will have been fulfilled.

The post A Celebration of the Ideal Bachelor From 1906 appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

0 Commentaires