Have you ever noticed that at your office or church, a small fraction of people do the lion’s share of the work?

This is just one manifestation of what’s called the “80/20 rule.”

Once you understand the 80/20 rule, you’ll start seeing it everywhere.

And be able to use it to significantly improve your life.

The Birth of the 80/20 Rule: The Pareto Principle

In the late 1890s, an Italian economist named Vilfredo Pareto observed a curious relationship between wealth and population in Italy. His calculations showed that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by just 20% of the population. He did similar surveys in other countries and found the same ratio.

Pareto kept digging, and he kept finding this 80/20 relationship between landownership and total population. It didn’t matter if he looked at a country’s land ownership data in 1890 or 1790. No matter the time period, 80% of the land was owned by just 20% of the population.

Pareto didn’t pursue or publicize his discovery, so it died in obscurity. It wasn’t until after World War II that Pareto’s 80/20 observation started to get the attention it deserved, thanks to a Romanian-born U.S. engineer named Joseph Moses Juran. Juran had read about Pareto’s 80/20 discovery and thought it could be applied beyond land ownership, including in the manufacturing industry.

In 1951, Juran wrote a management manual called the Quality Control Handbook in which he referred to Pareto’s discovery as the “Pareto principle.” He observed that the Pareto principle operated in crime, accidents, and as he had suspected, manufacturing. In the book, Juran notes one example of how a paper mill discovered that a small number of defect types — about 12% — created 80% of the costs for the company. When the mill focused on reducing defects in that 12%, they drastically reduced their overall costs.

American companies didn’t pay much attention to Juran, but Japanese companies rebuilding after WWII did. Like the American-born but Japanese-implemented idea of kaizen, Juran’s Pareto principle took hold in Japanese manufacturing firms in the 1950s and 1960s, helping Japan become an economic juggernaut. And just as U.S. manufacturers brought kaizen back to American shores to help slumping sales in the 1970s, U.S. companies eventually started applying the Pareto principle too.

Economists began studying the principle in earnest in the second half of the 20th century and discovered that you could see it across many domains in life.

In baseball, ~20% of a team’s players contribute to ~80% of its wins.

In movies, ~20% of films produce ~80% of total box office earnings.

In retail, ~20% of all products generate ~80% of a business’s revenue.

In computing, ~20% of software code contains ~80% of its errors.

You get the idea.

In 1997, entrepreneur Richard Koch published The 80/20 Principle in which he explained the Pareto phenomenon and showed how it can be applied not only in business but in your personal life. He’s credited with popularizing the Pareto principle, or 80/20 rule.

The 80/20 Rule in a Nutshell

In his book, Koch gives this definition of the 80/20 rule:

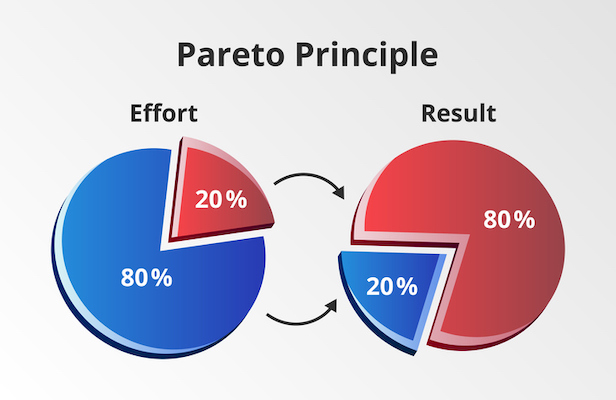

The 80/20 Principle asserts that a minority of causes, inputs, or effort usually lead to a majority of the results, outputs, or rewards.

In an even tighter nutshell: The 80/20 rule states that about 20% of causes produce about 80% of outcomes.

What this means is that not only does a small proportion of your efforts generate the great majority of your results, the great majority of your efforts are essentially useless. As Koch puts it: “80 percent of what you achieve in your job comes from 20 percent of the time spent. Thus for all practical purposes, four-fifths of the effort—a dominant part of it—is largely irrelevant.”

Don’t get too hung up on the exact 80/20 numbers. You don’t see everything break down perfectly into that ratio. The big takeaway from this is that, in the words of Juran, “the vital few” produce the lion’s share of results in life.

How to Use the 80/20 Rule to Improve Your Life

Every person I have known who has taken the 80/20 Principle seriously has emerged with useful, and in some cases life-changing, insights. —Richard Koch

Like I said, once you understand the 80/20 rule, you start to see it everywhere.

About 20% of my contacts make up about 80% of my texts.

About 20% of the companies I do business with get about 80% of my expendable income.

About 20% of the people in my social network cause about 80% of my personal problems.

Koch argues that by recognizing the 80/20 rule in your life, you can start making decisions to maximize utility and minimize pain.

In implementing the rule in your life, keep these two overarching principles in mind:

- If 20% of causes/inputs/efforts create 80% of the good things in your life, increasing the amount of time/energy/attention you give to that 20% will have a disproportionately large effect on increasing the positive quotient in your life.

- If 20% of causes/inputs/efforts create 80% of the bad things in your life, minimizing the time/energy/attention you give to that 20% will have a disproportionately large effect on minimizing the negative quotient in your life.

Here’s how to put these principles to work:

Time management. You can see which activities provide the most bang for your buck by tracking how you use your time. You’ll likely find that just 20% of your work tasks generate 80% of your results. So, spend more time on that 20% which gives you the most ROI while reducing the time spent on other, superfluous stuff.

Decluttering. Just a few of your possessions likely get the lion’s share of your use. Pay attention to what you use the most, and chuck the rest. For example, only a handful of items in my wardrobe get used regularly. So once a year, I’ll go through my closet and ask myself, “Have I worn this piece of clothing in the past year?” If not, it gets packed off to Goodwill.

Money. Start using a money tracking service, like Mint. After a month, review it. You’ll likely notice that a small percentage of businesses/services get the majority of your money. Find ways to reduce expenses on those “vital few” to dramatically reduce your overall expenditures.

Personal finance expert Ramit Sethi calls this going for “big wins.” Instead of worrying about trying to shave pennies off every.single.purchase, find ways to shave big chunks off the few categories creating most of your expenses. Eliminate credit card debt, look for ways to save money on rent and groceries, cancel subscriptions you don’t use anymore, etc.

Relationships. I bet if you were to do an inventory of your relationships, you’d find that just 20% of your relationships produce 80% of your overall happiness. Spend more time with these vital few.

I bet you’ll also discover that 20% of your relationships cause 80% of your interpersonal headaches. Spend less time with these annoying stress-stimulators, curbing your contact not only with people you actively dislike, but those you feel ambivalent about as well.

Leadership. If you lead people at church or in some other community, you’ll see the 80/20 rule in play: about 20% of the members of a group will do about 80% of the overall work. Knowing that, make sure you take care of those vital few. Appreciate them. Publicly recognize their efforts. Check in on them regularly to ensure that they’re not burning out or feeling resentful about the disproportionate load they’re carrying. If you can’t do away with the necessity of that load, at least try to lighten its weight; that is, if a task needs doing or a role needs filling, a 20%-er is probably going to have to do it, but is there a way to make that task/role simpler, easier, and less time-consuming and stressful?

When you’re part of an organization, you’ll likely also notice that about 20% of its members cause 80% of its problems. Do what you can to mitigate their influence on the community, but don’t spend too much time on them. Spending 80% of your time strengthening and encouraging the 20% of awesome go-getters will yield far greater fruit than spending 80% of your time cajoling slackers and putting out fires.

The post Improve Your Life With the 80/20 Rule appeared first on The Art of Manliness.

0 Commentaires